Back in 1995, when I was a high school punk rocker, my friend Sara turned me on to the Krishnacore band Shelter. Of course, Krishnacore wasn’t really a thing yet, as Shelter blazed the trail. Their leader, Ray Cappo, had previously founded the influential straight-edge hardcore punk band Youth of Today. Shelter added a transcendental religious element to Youth of Today’s already positive message. I was straight-edge and religious, and in addition to their music, Shelter’s message appealed to me. I didn’t know much about Eastern religions, but I was definitely intrigued.

Fast-forward over 25 years, and my friend & colleague Alex went on a Wisdom of Sages retreat to Florence. And as I was looking at his photos, I realized that the leader of his retreat was none other than Ray Cappo, leader of Youth of Today and Shelter, although he now went by the name of Raghunath.

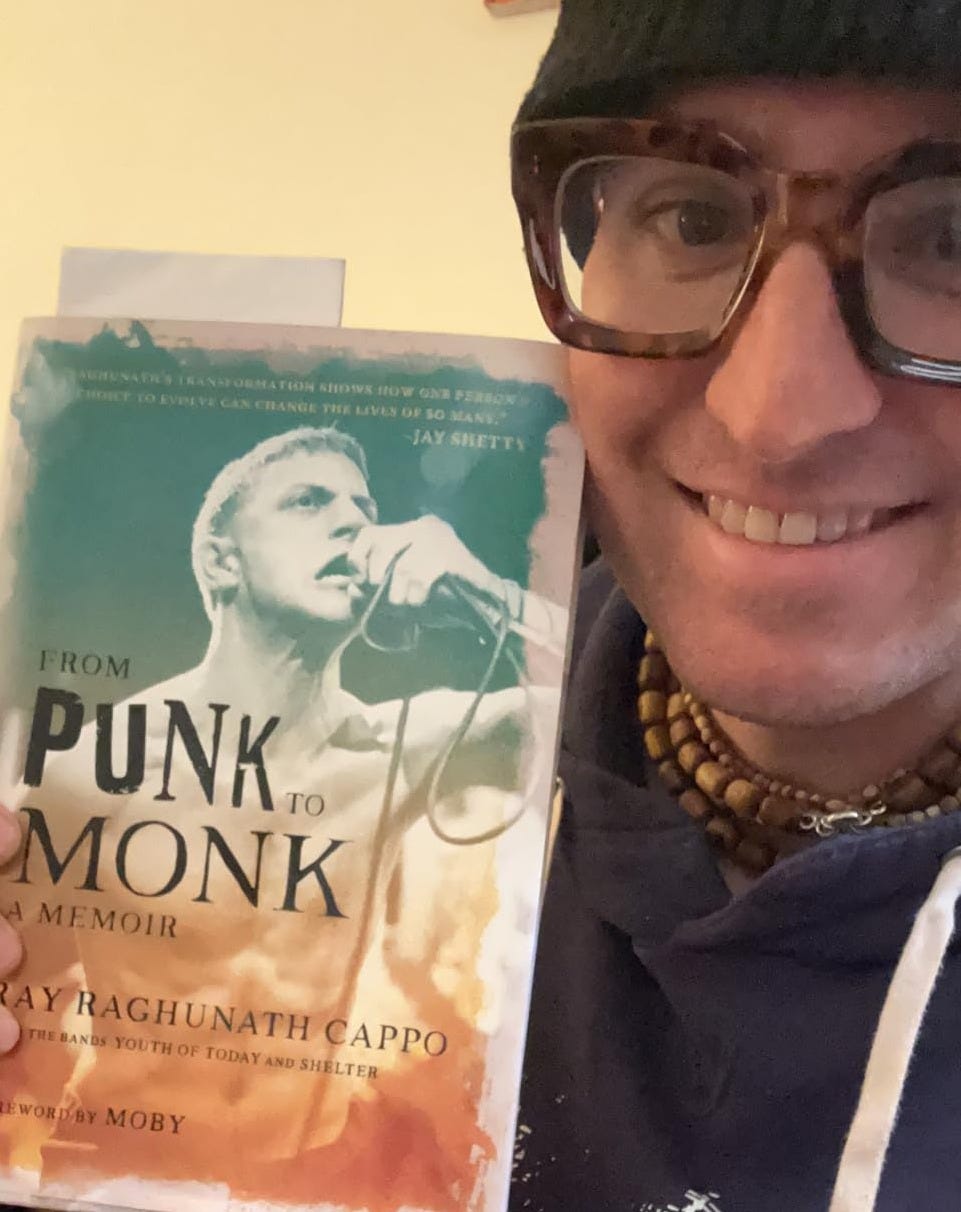

A year later, Alex tells me that Raghunath is publishing his memoir, From Punk to Monk: A Memoir. And then Alex shows up at work one day with a copy for me. (I stumbled upon Alex’s verified purchase photo with his review of the book on Amazon. See below. Lol.)

I always have more books than I know what to do with, so it sat on the shelf for months, but I finally picked it up last week. It was a quick read. I couldn’t put it down and finished the 342 pages in under two weeks. Raghunath’s stories are gripping, with wisdom and teachings sprinkled throughout. I give it 5 Stars.

The book begins in 1988, with the 22 year-old Cappo in India after his father died. He was by all accounts successful. His band Youth of Today had a large and growing following, and the label he started had signed twenty bands. But Cappo left New York City and the hardcore punk scene he helped build to travel halfway across the world become a Hindu monk.

“I didn’t lament giving up my previous life as a frontman,” writes Raghunath. “In return, I’d received the greatest gift I could give myself: a rebirth.”

One of his first lessons was this: “One person with a good attitude can change many.”

Cappo was on a miserable twenty-five hour train ride, travelling with a few other monks, in a packed car with no air conditioning. His initial stay in Krishna’s homeland of Vrindavan, in Northern India, was a failure, and some older monks had recommended that he relocate to the East, to Kolkata.

After the train breaks down, Cappo starts feeling sick — and begins to lose his patience. One of his fellow monks has an idea: “We must make the entire train chant the Mahamantra!”

“I was shocked,” recalls Cappo. “Not because he was dancing freely and joyously, indifferent to public opinion. No, I was shocked because people started singing along. This would never have happened on New Jersey Transit.”

Cappo reflects on watching the mood of the entire train change: “The sounds that are in your mind and flow out of your mouth will make you joyous or miserable.”

The second chapter jumps back in time to the early-’80s, when Cappo was in high school, discovering the small punk rock scene in his Connecticut hometown — and travelling about 90 minutes down to New York City.

Reading the chapter, images popped into my head from my local punk scene in Warner Robins, Georgia, and travelling up to the larger scene in Atlanta. My first local punk show, headlined by Smack, as well as a couple of my friends’ bands like Armored Bus. My first “big” punk show in Atlanta, headlined by MxPx. Convincing my church to host a punk rock show, headlined by Atlanta band 7-10 Split, with Offcenter, whose bassist was in the church youth group with me, opening. Convincing the Jaycees, a non-profit civic organization, to rent out their building for another 7-10 Split show, with Offcenter and Florida punk band Atonal Spiral, that brought 500 people.

It was an exciting time for me, so Cappo’s stories from the early New York punk scene really hit home. His stories helped make mine possible.

But the music is only half the story. In fact, the music is not even half the story. The real story is the message.

With his father in the ICU, Cappo had an epiphany. “I realized that the real question wasn’t about when I was going to die. It was about what I was supposed to do while I was living.”

In time, he found the band Youth of Today, which helped the budding straight-edge scene “become an international movement — a positive subculture within the nihilistic scene of American punk and hardcore music.”

Cappo helped build a movement dedicated to abstinence from drugs and alcohol, combined with vegetarianism. But it wasn’t enough: “I was feeling a little sad, a little empty, hankering internally for something. There was a God-shaped hole in my heart, and I was trying to put things in that hole that didn’t fit, like popularity and validation.”

“The straight-edge principles of self-control,” writes Cappo, “were incredibly important, but they were the threshold to something more esoteric and metaphysical.

Soon, he met Harley Flanagan of the band Cro-Mags, who introduced him to the Bhagavad Gita and the teachings of Krishna. Cappo notes the irony: “This was my introduction to Vedic thought and the bhakti tradition. Not through a swami, sage, hermit, or guru, but through a teenage gang member and part-time transcendentalist. … The universe chooses perfect messengers for us when we become seekers.”

And that’s a key theme throughout the book. As he reflects towards the end of the book: “I realized that messengers had always been sent to me, but sometimes I simply couldn’t and wouldn’t hear from them.”

One person the universe put in Cappo’s life that he did listen to was Steven Rosen, or Satyaraja Das, who asks: “Okay, Ray, next time you’re on stage, see if you’re doing it to serve God or to be God!”

It was a humbling question. Youth of Today had just signed to a major record label, but Cappo’s heart wasn’t in it anymore: “I wanted to detox from the world of hardcore music. … Any fame I got with the band was not making me a better person; it was merely amplifying my ego and my entitlement.” So after the band’s biggest tour to date, Cappo quit the band to travel to India and become a monk.

Then he learned that his father had died.

Being a monk wasn’t easy, but Raghunath calls it one of the best decisions he ever made. “I thought about my previous life in New York. I didn’t drink, smoke, take drugs, or eat animal products, but I didn’t have this sweetness.”

What led to this sweetness?

“I realized,” writes Cappo, “that most of the pain in my life came not from the physical world but from the mental world. … Yoga practices existed to help our minds become more peaceful.”

More specifically, Cappo had to learn to control — to change — his judgmental attitude. And he learned a big lesson to that end on that long train ride to Kolkata from an elderly man who sat next to him and tells him a story. The man then explains the story: By criticizing others, you judge yourself. Why? “Because they are relishing a person’s poor choices,” he says. “They are thinking themself superior to the culprit, and they are not. They themselves are just a moment away from a poor action.”

And so, before they part ways, the man says this: “My dear, if you will add something to your life, just do this one thing: Give up the desire to find fault with others and try to find their good instead.”

We would all be better off if we could find such sweetness.

It took Cappo a while longer — and a humiliating experience — for the lesson to really sink in.

Cappo lived as a monk for six years.

In the meantime, he discovered that he had a different calling: “The more I studied these Vedic teachings the more I understood the true middle path. It was not a renunciation of our gifts. It was using our gifts in a divine way. To renounce would be a disgrace. A dis to God.”

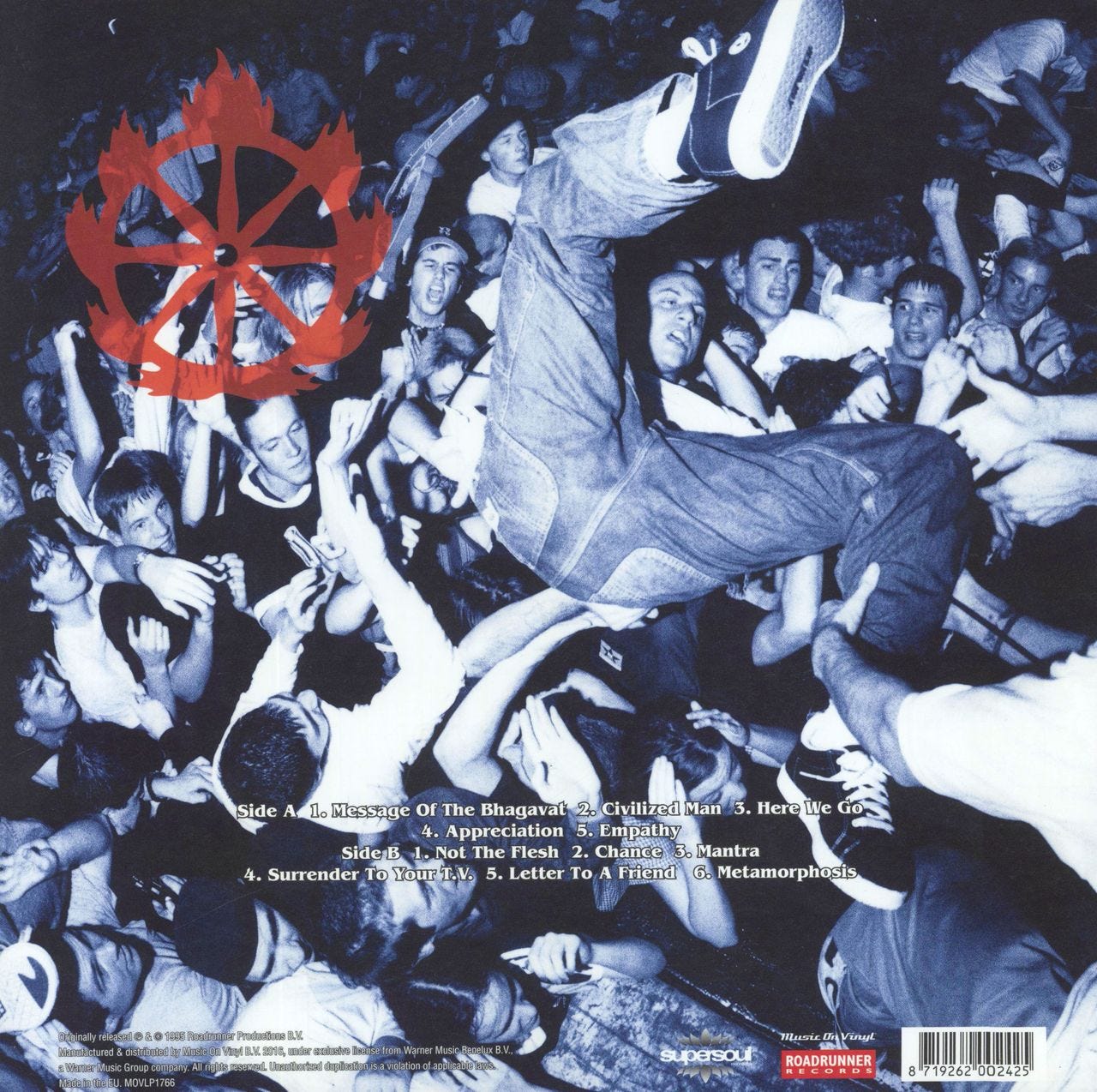

And so, “I did something unprecedented in the sacred bhakti lineage — I started a band, a punk/hardcore band of celibate monks and Krishna devotees.”

That band was Shelter, and they were based out of an ashram in Philadelphia. “Our agenda,” writes Cappo, “was no longer about us. It was no longer about being the center; it was about serving the center.”

Shelter travelled to India, where Cappo received the name Raghunath Das. “I loved my new name,” he says. “It gave me a new sense of identity from my past.”

And on another twenty-five hour train ride, Raghunath proved that he was a new person. Frustrated by a drunken man, “I had to remind myself that there was a new incarnation of myself that I was trying to step into.”

“Compassion. Tolerance. Love. That was my only job.”

Lesson learned.

But now he had to learn to live in the world, outside of the ashram and the protections it provides: “Would I use that gift to serve God or to be God? This was the only question I needed to answer.”

Once again, Raghunath looked for teachers: “Having leader that you can look up to is important. We tell ourselves to be our own heroes, but we miss out on a valuable lessons taught by people who have walked these roads before us.”

Reflecting at the end of the book, Raghunath asks: “How can I ever pay back all the people, teachers, and caregivers who have touched my heart with this spiritual magic?”

His answer: “I cannot pay them back. I can only pay it forward.”

This book is one important way Raghunath has paid it forward. I definitely recommend it. The stories — and there are so many — are so rich.

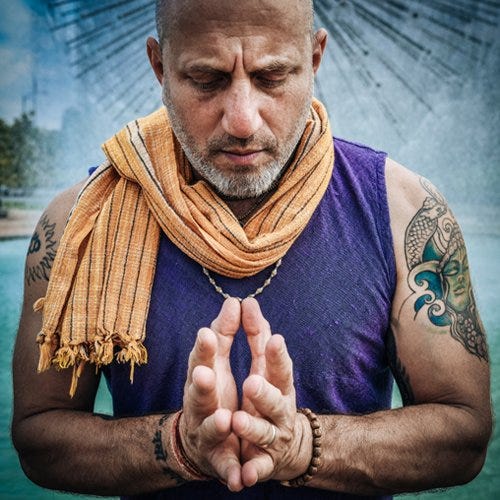

Raghunath also runs a retreat center in Upstate New York called Supersoul Farm, cohosts the #1 spirituality podcast Wisdom of the Sages, and leads pilgrimages to India each year.

He is paying it forward, again and again and again. Thanks be to God.

![Youth Of Today [Official] Youth Of Today [Official]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F16b0d723-95c2-4f35-9c24-2e9875085b04_343x147.jpeg)

I ordered this book a few how’s before stumbling across your review. I’m looking forward to reading it.