As I’ve mentioned before, I didn’t read much growing up. Even still, I remember pretty much everything I was supposed to read and everything we read together as a class.

I’ve also been in education for over a dozen years, and I led a team in building curriculum for a series of reading intervention and enrichment modules for middle school students reading from a 1st grade level up to an 8th grade level.

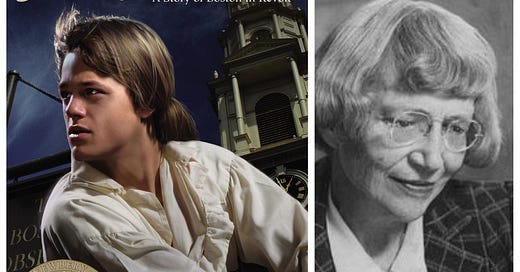

But I had never heard of Johnny Tremain until I moved to my current school.

It’s historical fiction, which is the kind of thing I might have been interested in as a child. I enjoyed nonfiction, biographies especially, and I never understood the point of fiction. But fiction was all we read in school.

Historical fiction appeals readers of all kinds. It’s a good way to embed historical content in narrative for those who prefer fiction, and it’s also a good way to teach reading comprehension skills for those who prefer nonfiction.

Set in Boston during the time leading up to the American Revolution, Johnny Tremain tells the story of a boy who gets involved with the Sons of Liberty — in the shadows of founding fathers like Paul Revere, John Hancock, and Samuel Adams.

At the beginning of the book, Johnny is a talented — and arrogant — apprentice. But when the skilled silversmith suffers an injury to his hand, his future is bleak.

He stumbles into a job delivering a Whig newspaper, though, and begins carrying letters for both Whigs and the British as well. He soon finds himself immersed in a world of revolutionary politics.

Unable to enlist as a soldier because of his injured hand, Johnny finds his own way to fight for the cause of liberty by delivering secret messages. He even participates in the Boston Tea Party. And his most important message is to tell the sexton whether to hang one or two lanterns (as in, one if by land, two if by sea) at Christ’s Church.

The big message of the book, though, is why they fight.

The firebrand Sam Adams offers the more simplistic answer: “We will fight for the rights of Americans. England cannot take our money away by taxes.”

The esteemed elder James Otis counters: “No, no. For something more important than pocketbooks of our America citizens.” He offers a broader vision: “The peasants of France, the serfs of Russia. Hardly more than animals now. But because we fight, they shall see freedom like a new sun rising in the west.”

He continues: “We give all we have, lives property, safety, skills…we fight, we die, for a simple thing. Only that a man can stand up.”

It’s not lost that Forbes published the book in 1943, during World War II. But while the book is certainly patriotic, it’s not simplistic. The British are not evil; they are, in fact, quite accommodating to the rebellious colonists — a point Otis stresses in his speech. Nor are the Americans pure in spirit. Most are everyday people, concerned more with their daily lives and making ends meet than the political machinations of the elite, many of whom try not to take a stand either way, neutrality being more profitable. And even though the wise old Otis offers the most important ideas of the book, Sam Adams and the other leaders blow him off.

A major criticism is the way Forbes presents the few Black characters in the book. Jehu, “Mr. Hancock’s little black slave,” is described as “a tiny African.” And an unnamed enslaved person is described as a “skinny, slippery-looking old black slave.” Lydia, the “handsome black washerwoman,” is presented as comically ignorant: “Don’t know commandeer, but it sounds dreadful cruel to me” and “My land, boy, don’t you let them cook that pretty horse of yours.” Still, she plays a key role for the rebellion. Miss Bessie is the most prominent — and the most complex — Black character. Forbes describes her as “that ‘monstrous fine woman.’” A Whig, she also plays a role in the fight against the British, but she stays loyal to her Tory employees.

But it’s worth exploring how Johnny’s attitude around race changes over the course of the book. After his injury, he learns some humility — and he goes from looking down on Jehu to teaming up with Lydia and Miss Bessie.

Johnny Tremain is a classic — and the book won a Newbery Medal. While there needs to be discussion around race in the novel, and while it’s a bit long, I don’t know of a better book for learning about the events leading up to the Revolutionary War. In my experience, kids love it.

I give it 4 Stars.